Why gas stoves contribute to climate change

It’s the thousands of miles of pipeline infrastructure behind the gas system

Photo by the author.

You may have heard the news about gas stoves – more and more, there are articles coming out about how burning methane gas indoors is bad for your health, whether it’s about inhaling benzene (linked to cancer) that’s in that fossil fuel gas or asthma cases linked to the indoor air pollution from gas stoves. If you like podcasts, this episode of Volts discusses gas stoves in detail.

You may be wondering – OK, gas stoves may be bad for your health, but are they really a big contributor to climate change?

I grew up with gas stoves, and used them for many years, and thought they were fine. That is…until I learned more about them, and the massive amount of expensive yet invisible infrastructure that is underneath our feet, and how much this infrastructure contributes to climate change.

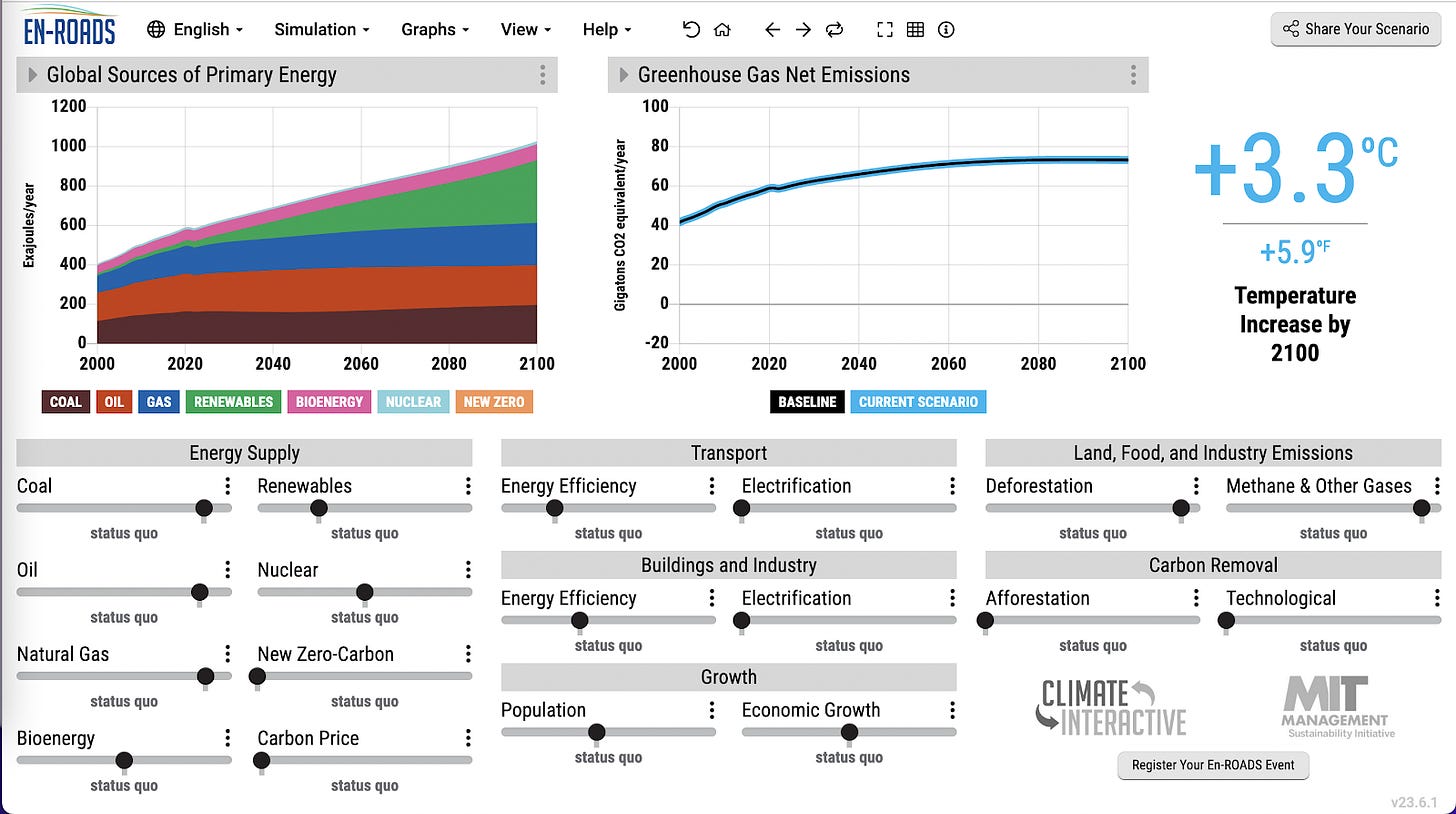

I recently completed the 12-week Terra.do course on climate change, called Learning for Action, and one of the activities we got to do was the EN-ROADS Simulator, where you can try to “pull some levers” to see how to get to a 1.5 degree Celsius future warming (vs. the 3.3 degrees C that we are currently on). While that may not sound like a big difference, if you think about the human body, a 0.8 degree C difference between 37C) – what might seem like very small amount of temperature difference – is actually a fever, according to the Mayo Clinic. By that metric, the Earth already has a fever: we are already at 1.1 degrees C of global warming, according to measurements taken since 1880.

That means that we need to do everything we can to stop the fever from getting worse, and hopefully reverse it.

If you play with the EN-ROADS simulator, which is actually kind of fun, you’ll see that “Buildings and Industry” are two of the levers in the model. Accordingly, building electrification is one of the pieces of the solution to climate change.

If you toggle both of those levers to “high” – it can have a 0.5 degree impact towards fixing climate change:

BUT as you see, no one of these levers is a silver bullet.

We need a combination of things to get to a better future. And, we can mitigate global warming to less than 1.5 degrees C if we really push the envelope: here is an example scenario like that

Gas Stoves, Economics, and Climate Change

The U.S. alone has nearly 3 million miles of methane (“natural” or fossil fuel) gas infrastructure. A lot of this infrastructure is literally rusting in the ground: some pipes in the Northeast are made of cast iron, for example, and are decades old. Google and EDF teamed up to make “methane maps” to help identify leak-prone pipes that’s still being used. Boston, Massachusetts, for example, has about one leak per mile of pipe. Nearly 68,000 miles of leak-prone pipe are still in use in the US, according to EDF. Considering that methane gas has a global warming potential of 28-87x more potent than carbon dioxide, methane gas leaks matter to climate change.

You might wonder: does consumption of gas impact utilities’ profits? Actually, not really, because it’s about that invisible infrastructure underneath our feet that

Here’s a quick recap of the economics of the fossil gas system:

Gas utilities are regulated monopolies. Rate-of-return regulation determines cost of providing service by utility to allow them to recoup those costs plus a return on their investment. The cost of getting a new household on the gas system is spread across all customers, thereby reducing the cost of expansion. Gas utilities’ primary profit derives from capital expenditures: Your using gas in your stove, i.e. consumption, does NOT have significant impact on utility profits.

The cost of setting up gas pipes is depreciated over many decades. But in New York state alone, there are 8,000 miles of leak-prone pipe. This is bad for safety, health, and emissions, because leak-prone pipe leaks. This is part of a broader issue of fugitive emissions – while your gas stove may not seem like it uses a lot of gas, gas stove leak methane even when they’re off, and so do the many miles of pipe that service them.

Gas companies are making money from fixing and replacing leak-prone pipe (which includes cast iron, steel, and early plastic pipes). The term “net salvage” on your utility bill is a prepayment for decommissioning and removal of gas lines, though often these gas lines aren’t actually removed at the end of their useful life. (Source: Future of Gas in New York State report) We could fix the leaks by replacing the pipes, but that won’t help us meet our climate action goals because that would lock us in to decades more of using fossil fuels – when we want to be reducing, not increasing, their use.

So what’s the deal with methane “natural” gas use in buildings, like for stoves?

An example of a 120-volt induction stove with a battery built in, that reduces or eliminates the need for rewiring one’s kitchen to accommodate a traditional 240v induction stove. Photo © Katharine Bierce, 2023.

Upgrading Homes is Cheaper than Upgrading Aging Gas Pipelines

As noted in a recent webinar by the Building Decarbonization Coalition with Groundwork Data about the Future of Gas in New York State report, gas distribution is 25% of New York State’s greenhouse gas emissions (as noted in their webinar summary.

Today, due to the age of the gas system, nearly 9 out of every 10 miles of distribution mains in New York installed are replacements (source: the Future of Gas in New York State report). The report notes:

While replacing old pipes improves system safety and reduces fugitive emissions, the average cost to gas utilities of doing so has ballooned to $3 million per mile. When calculating what will actually be sought from ratepayers, the costs more than double due to taxes, depreciation, and the regulated rate of return investors receive. As a result, today, every time a mile of gas main is replaced, the average cost to do so is over $60,000 per ratepayer serviced by that line. It is unreasonable to expect that these costs can be recovered from ratepayers over many decades. Both climate laws and competition encourage gas ratepayers to opt for alternatives.

Recovering the cost to replace old methane gas pipes at $60,000 per person, or even per household, is INSANE.

$60,000 per household is more than a new car.

If you think about how much it would cost to mo get a heat pump water heater, a heat pump dryer, a heat pump to replace a furnace and A/C with one system, and an induction stove, including the labor to do that… you could probably make all those upgrades AND still save money. Heck, you could probably upgrade your insulation, too. And, if utilities did these upgrades neighborhood by neighborhood, you as a consumer wouldn’t have to pay any more, because utilities could take that $60K they’d spend on replacing gas mains and they could GIVE you appliances FOR FREE.

Low-income households are disproportionately affected by increasing costs of energy if wealthy people move off gas infrastructure on their own. This is why we need to think about upgrading entire neighborhoods, such as leveraging the future gas pipeline replacement/maintenance costs to upgrade appliances NOW.

A portable 120-volt induction wok, from the free Ava Community Energy induction cooktop lending program.

Photo © 2024 by Katharine Bierce

What we can do to decarbonize buildings with equity and justice in mind

Fortunately, some utilities are already doing pilots to make these upgrades in disadvantaged communities and helping make building electrification part of their long-term strategy. Check out this 2022 webinar on Zonal Electrification with PGE for more:

We can’t reach our climate goals without including upgrades to building infrastructure, which means getting rid of the gas system and upgrading people to cleaner, more efficient, and better systems like heat pumps and induction stoves.

While I used to cook with gas, now that I know better, I know that induction stoves are 3x more efficient than gas and also boil water in half the time. Someday I hope to buy a house and the stove I hope to get is an induction stove with a battery built in. ‘

P.S. The three companies making 120v induction ranges coming to market in 2024 are:

Copper Home (formerly Channing St Copper) (Berkeley based)

Cooktop plus oven

Shipping in 2025

Offering a 1-year warranty

$5,999

Impulse Labs (San Francisco based)

Cooktop only

Shipping fall 2025 (delayed due to tariffs)

$4,999 preorder, $5,999 regular

No warranty info available on the website; battery replacement “upon request”

Electra (New York based)

Cooktop plus oven

Expected Aug-Dec 2024

Offering 10-year warranty on the battery

$3400 list price

Want to learn more? See why Chef Curtis Stone loves induction in this ~30 second YouTube video.